How can California pay for wildfire prevention at scale?

To reduce the risk of catastrophic wildfire, California must invest billions of new dollars each year into key actions including forest thinning, prescribed fire, defensible space, home hardening and more. Yet for all of our ambition, a key question remains: where does the money come from?

In this technical blog post, we analyze five potential state-controlled funding options, including: (i) Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund revenues; (ii) avoided wildfire carbon credits; (iii) vehicle miles traveled mitigation banks; (iv) new insurance mechanisms; and (v) a new biomass economy. We find that while each option has potential in different settings, a new biomass economy producing high-value products from wood waste may be the only option capable of supporting forest treatments at scale. VMT mitigation banks could also be effective for incentivizing buffer zones in wildland-urban areas, such as Greater LA and the Bay Area. GGRF can provide near-term support in both cases. We identify policy needs to enable a sustainable forest bioeconomy and VMT mitigation banks in California. Importantly, both strategies are policy focused and would require little, if any, support from the General Fund.

***

From 10,000 feet above sea level in the Sierra Nevada mountain range, to Malibu and the Pacific Palisades west of LA, it feels like no corner of the state is immune to catastrophic wildfire. Since 2018, hundreds of Californians have lost their lives to multiple severe wildfires, alongside tens of thousands of destroyed structures and hundreds of billions in damages. In the process, wildfires have become one of the state’s largest greenhouse gas emissions sources, where in 2020 alone a handful of megafires emitted more carbon than the state has been able to reduce since the passage of AB 32 in 2006.

State experts have identified what needs to be done to address the wildfire problem: an enormous expansion in the pace and scale of forest treatments to reduce fuel loads as well as widespread home hardening and defensible space initiatives in the wildland-urban interface. The state has committed to implementing these measures, but a key question remains: how do we pay for them?

It is estimated that $3-4 billion would be needed annually to implement the state’s goal of treating 1-2 million forested acres per year.[1] We estimate that another $3 billion annually could support community resilience in the wildland-urban interface. This totals $6-7 billion in annual new investments for wildfire prevention that would need to be maintained for multiple decades. For context, this amount is higher than the entire California Natural Resources General Fund budget allocation in 2024-25, which totaled $5.4 billion, covering a range of issues including firefighting (roughly 50% of the entire allocation and growing), drought, flood, sea-level rise, extreme heat, 30x30, and more. The $1.5 billion for wildfire prevention in Proposition 4, which is essential initial funding, would nevertheless provide less than 3-months of support for forest treatments and community resilience if implemented at scale.

The arithmetic is straightforward: California must find new, large and reliable resources to stand-up a credible wildfire prevention program that meets the scale of the problem. In this blog, we provide a high-level evaluation of five state-controlled alternatives outside of the General Fund. We note that this is not an exhaustive list but hopefully captures some of the main options for stakeholder consideration.

Alternative funding options

We evaluate five alternative funding options based on their reliability, referring to how reliably we can count on that funding source being available in a given year, and scalability, referring to whether the strategy on its own is substantial enough to support wildfire prevention efforts at the multi-billion dollar annual scale. The alternative options evaluated include: (i) Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund revenues; (ii) avoided wildfire carbon credits; (iii) vehicle miles traveled ("VMT") mitigation banks; (iv) new insurance mechanisms; and (v) establishing a new biomass economy. A summary of our perspective on the reliability and scalability of each of the options is provided in the text and Figure 1, below:

Figure 1: This diagram summarizes five potential wildfire prevention funding options based upon their reliability and scalability. While all options have some potential, we find that (i) a new biomass economy, and (ii) VMT mitigation banks are the most reliable and scalable options. A new continuous appropriation within GGRF for wildfire prevention could provide reliable near-term funding as biomass and VMT strategies are brought to scale.

Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund

California’s Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund (GGRF) generates around $4-5 billion per year from Cap-and-Trade auction proceeds for re-investment into climate action. 65% of this total amount is automatically appropriated each year to key programs including High-Speed Rail, Affordable Housing and Transit. The remaining 35% is appropriated on a discretionary basis to a variety of climate programs. Wildfire prevention has, in general, received an increasing portion of discretionary funding in recent years, including as high as $483 million in 2021-22. However, it was only $92 million in 2023-24.

GGRF could be a reliable source of funding for wildfire prevention provided it becomes a continuous appropriation. There is potential to consider this change as part of cap-and-trade reauthorization. GGRF alone is unlikely to be a scalable option due to additional priorities that are expected to share in the funding, including a variety of needed clean energy technologies and infrastructure. Overall, GGRF could provide a reliable and moderate amount of base funding while other options are brought to scale.

For more information, see our Data analysis of California’s Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund. Note that the above wildfire prevention estimates exclude other forestry projects that also receive funding under GGRF, including reforestation, avoided conversion, and other forest management.

Avoided wildfire carbon credits

Forest management protocols that credit carbon sequestration are widely employed as a way to help finance forest management. One of the key challenges in California is that needed fuels reduction actions (thinning, prescribed fire) result in carbon emissions as opposed to sequestration. As an alternative, researchers have sought to develop new protocols that would credit avoided wildfire emissions from fuels reduction projects. In these protocols, which rely on substantial computer modeling, the credit is equal to difference in wildfire emissions between a treatment vs. no treatment scenario.

Figure 2 shows a case study application of the Reduced Emissions from Megafires protocol, developed by Climate Forward. Note that despite the consideration of avoided wildfire, the protocol shows it could still take multiple decades to increase the carbon stock in the forest. The result is that a key feature of avoided wildfire proposals is that the credit would be awarded immediately following the completion of the fuels reduction project and before the carbon stock is actually measured to have increased in the forest, with a goal of generating revenue more quickly to support the cost of the forest treatment.

Figure 2: This figure shows a case study of the Climate Forward protocol (Buchholz et al., 2021). The results show that, even after accounting for avoided wildfire emissions, it could take roughly 40-years to increase the carbon stock in the forest. This case study shows a roughly 5 tCO2e/acre net-carbon benefit, which is not substantial, although it's possible under different assumptions this number could be higher and the net-carbon benefit forecast to occur earlier.

It is difficult to determine the reliability and scalability of avoided wildfire carbon credits. Today, they are neither available as a compliance instrument at CARB, nor, as far as we know, in the voluntary carbon market. The notion of awarding the credit before the measured increase in carbon stock constitutes a paradigm shift in carbon offsets, where the credit would be based purely on computer modeling. Moreover, even if developers could wait the period to measure the carbon stock change in the forest, the credit would still depend on significant uncertainty in the modeling, where changes in key variables, such as wildfire probability, have enormous impacts. The result is that, for this analysis, we consider avoided wildfire credits as having relatively low reliability. Technically, the scalability could be relatively high, but this would depend on adopting optimistic assumptions in the modeling, such as high wildfire probability.

VMT mitigation banks

One of the key lessons out of the recent Palisades Fire was the importance of community resilience strategies, such as buffer zones, to reducing wildfire severity in urban areas. Local governments with land-use authority have the potential to implement these strategies, but have historically had limited incentive to do so, as natural and working lands do not generate the same amount of local tax revenue that can support local priorities as compared to residential property development. This is also a key reason why Sustainable Community Strategies have fallen short of implementation goals to date.

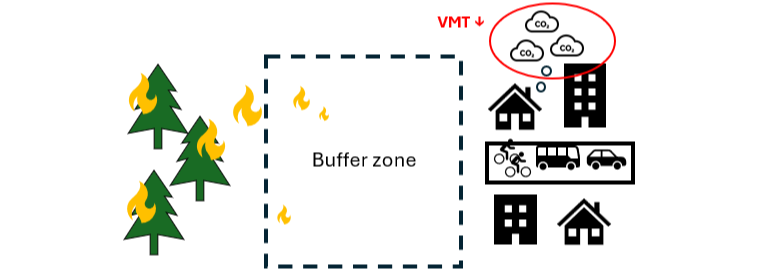

California could establish a new incentive regime that enables buffer zones on urban peripheries by crediting the avoided VMT that would have otherwise occurred had those lands been used for residential development. These would be known as VMT mitigation banks. The way it would work is as follows: local governments, conservation organizations, or other interested groups could identify and retire open space on urban peripheries with a quantification of the avoided VMT had the lands otherwise been developed under a business-as-usual scenario. Separately, land-use development projects in the region that are required to mitigate their environmental impacts under CEQA, including greenhouse gas emissions, could purchase credits from the bank, in doing so helping to finance the original conservation action. The Sustainable Agricultural Lands Conservation program, one of the highest-performing GGRF programs, is an example of a program that quantifies avoided VMT from land conservation in California.

Figures 3a, 3b and 3c illustrate how the credit generation would work. Previous research from ICF suggests that a new $400M annual income stream could be generated for projects such as buffer zones via this approach. (Although this analysis, commissioned in 2018, assumes a conservative carbon price of $11/ton, indicating the potential for far greater than $400M per year). The result would be a reliable and scalable funding source for urban areas where large avoided VMT could be identified. In the next section, we identify two broad policy needs to enable this wildfire prevention solution.

Figure 3a: This diagram shows the current day scenario with the urban periphery at risk of development.

Figure 3b: This diagram shows the baseline scenario of residential development, including increased VMT and wildfire risk.

Figure 3c: This diagram shows an alternative scenario where the at-risk lands are retired and placed under a conservation easement, reducing VMT and providing a buffer zone against wildfire risk. This land-use strategy is incentivized by quantifying the avoided VMT (compared to 3b) and selling the credits to buyers needing GHG mitigation under CEQA.

New insurance mechanisms

New insurance mechanisms have emerged as a potential tool to fund wildfire prevention. These mechanisms would work by quantifying the premium savings associated with fuels reduction compared to a no treatment scenario. The forecast premium savings would then be used to raise upfront capital via bond financing to pay for implementation of some portion of the forest treatment. As the treatments occur and savings are realized, the savings would be used to pay back bondholders.

These new approaches could be helpful, although there are a number of uncertainties and potential implementation challenges that make it difficult to determine their reliability and scalability. For example, if the above strategy were to be performed for a community (sometimes referred to as “community-based catastrophe insurance”), the city or county would likely need to assess a new fee on residents equal to the premium savings to pay the debt servicing on the bond, which may be difficult to achieve voter approval. (This is because the savings are nominal only; the public agency still needs to pay a premium for the new insurance product, which would have been higher absent the forest treatment). Of course, if there is sufficient coordination such that homeowners recognize that they are benefiting from reduced residential insurance, they may be willing to accept a new fee. Other factors include that these mechanisms are more viable in specific settings, such as where communities or other key infrastructure is located, and so are unlikely to be scalable to the broader wildfire prevention need.

New biomass economy

A standard fuels reduction treatment will generate, on average, 10-15 dry tons of forest waste per acre.[2] At 1-2 million acres, this is equal to 10-30 million tons of forest waste per year. Currently, the state processes about 2 million tons of forest waste per year, half of which are mill residues. The main outlet is biomass combustion for electricity. The remaining residues are primarily field burned or left to decay in the forest, resulting in substantial carbon and air pollution. As the state ramps up its forest treatments, there is expected to be a significant shortfall in biomass processing capacity. In recent months, local governments, with limited state support, have turned to strategies including converting their waste from wildfire prevention into pellets to then export for combustion in power plants in the UK and Asia.

California could turn what is a rapidly growing emissions and air quality problem into a robust wildfire prevention solution that at the same time generates thousands of new in-state jobs, by establishing a new biomass economy. Specifically, the state could enable the deployment of a number of new and clean technologies that process biomass waste into high-value products, including building materials, clean fuels such as hydrogen, sustainable aviation fuel and renewable natural gas, and carbon dioxide removal. As these non-combustion options are significantly more valuable than current options, at scale they could plausibly offset the entire cost of forest treatments (Table 1). Certain options, such as clean fuels, already have large and existing end-markets; meaning that, provided policies can be instituted to enable technology deployment, there is a high potential for buyer offtake. Lastly, we note that each of the above technology options are identified in the 2022 Scoping Plan as playing a key role in achieving the state's goal of net-zero emissions by 2045 as well as the accompanying CARB Resolution 22-21 to cease biomass combustion and pursue non-combustion options going forward. In the next section, we identify key policies to enable a new biomass economy for wildfire prevention in California.

Table 1: This table provides a high-level estimate of potential revenue and net-profit associated with converting 15 dry tons of forest biomass wood waste into hydrogen with carbon capture and storage.

Activating scalable solutions

In the previous section, we identified (i) VMT mitigation banks, and (ii) a new biomass economy, as having the potential of serving as reliable and scalable new funding sources for wildfire prevention in California. In this section, we highlight key policy needs to activate each of these solutions.

VMT mitigation banks

There are two key and interrelated policy needs to establish demand – and a funding stream – for projects such as buffer zones on the periphery of communities in wildland-urban areas. These include:

Policy #1: Establish a net-zero greenhouse gas standard under CEQA. At present, land-use development projects that are required to mitigate their GHGs may meet a variety of different "significant impact" thresholds under CEQA, depending on the lead agency. For example, some projects may be determined as sufficiently mitigating their GHGs by achieving a 40% reduction by 2030. If, however, the state were to determine that all CEQA projects must mitigate to a net-zero GHG standard consistent with AB 1279 (Muratsuchi) and the 2022 Scoping Plan, this would significantly increase the demand for GHG mitigation options, including off-site options, as almost all projects will be unable to mitigate to net-zero with on-site decarbonization measures alone.

Policy #2: Establish new VMT reduction protocols that are authorized for compliance under CEQA. In this step, the relevant agency would establish protocols that quantify the GHG benefits of establishing buffer zones in urban areas, amongst other potential wildfire prevention actions, which could be certified as capable of meeting compliance obligations under CEQA. Strictly speaking, these protocols would measure the avoided VMT of rezoning lands on or around urban limit lines from residential development (Figure 3). Although this is a modeling activity it is a more straightforward calculation than, for example, probabilistic wildfire modeling, considered above.

As highlighted, a preliminary estimate from ICF is that this policy combination could potentially create hundreds of millions, if not billions, of dollars in new funding each year for buffer zones. Further research can refine this estimate. We anticipate that legislation is likely needed for policy #1, although its possible that regulatory measures would also be sufficient, given the state's clearly mandated climate goals.

New biomass economy

California has taken some steps to institute a new biomass economy, including by establishing a handful of initial grant programs. However, the scale of the problem far outstrips these starting programs. We identify a suite of potential policies that could be considered as part of broader plan and vision for a new, clean and innovative biomass economy in California that creates good-paying jobs and reduces emissions. These policies seek to address key barriers to deploying non-combustion technologies:

Establish procurement standards for wood products, such as mass timber, wood fiber and biochar, that can reduce the embodied carbon in construction materials and buildings. This could start with application to California State government infrastructure projects as identified by the Joint Institute for Wood Products Innovation.

Address key barriers to long-term feedstock supply from public and non-industrial private lands, including by performing regional biomass availability assessments and increasing funding to and expanding the Office of Land-Use and Climate Innovation’s feedstock supply program.

Develop a biomass tracking system to trace and authenticate waste biomass origins and assure environmental sustainability for the purpose of a range of new and existing programs and end-uses including wood products, clean fuels and carbon dioxide removal.

Develop an incentive pathway, such as a design-based pathway, and/or guidance under the Low Carbon Fuel Standard for fuels created using waste feedstocks from forest health projects. An existing life cycle assessment tool being further developed by the Schatz Energy Research Center and Cal Poly Humboldt may offer a starting point.

Develop and adopt biomass carbon removal protocols that identify eligible biomass carbon removal pathways for the purpose achieving the state’s carbon dioxide removal targets as identified in AB 1279 and the 2022 Scoping Plan.

For more information, see Addressing California's wood waste crisis, which provides further discussion on non-combustion product options and challenges with current technology options.

Conclusion

California faces an unprecedented wildfire crisis that is a significant threat to people and communities. State experts have clearly identified the actions needed at scale to reduce the risk of severe impacts. The key hurdle is that these actions will cost billions of dollars each year and need to be sustained for likely 2-3 decades. In this article, we evaluated five options for implementing the state's wildfire prevention ambitions outside of the General Fund. This is not an exhaustive list of the options, but is hopefully a useful start for stakeholder consideration. We identified (i) a new biomass economy, and (ii) VMT mitigation banks, as having high potential as sustainable and scalable funding sources for wildland and urban fire prevention. GGRF revenues could provide a reliable base of near-term funding as these options are brought to scale, but a new continuous appropriation would be required. Overall, we conclude that there do appear to be options to support the state's long-term wildfire resilience goals. New policies can enable these options while creating jobs and driving benefits throughout the state.

For more information, contact Sam Uden (sam@netzerocalifornia.org) and Amanda DeMarco (amanda@netzerocalifornia.org).

[1] California has established a goal to treat 1 million forested acres per year for wildfire prevention. Additionally, the 2022 Scoping Plan identified needing to treat 2.3 million acres per year to meet state climate goals. We therefore assume a goal of roughly 1-2 million acres per year. The main basis of the cost estimate is the Biomass in the Sierra Nevada report by Sierra Business Council, which estimates treatment costs ranging from $1,500 to $4,400 per acre for mechanical thinning and hauling and $300 to $1,800 per acre for prescribed fire. These estimates are consistent with estimates NZC staff continue to hear from practitioners in California. Note that steeper sloped terrain requiring the use of additional equipment would greatly exceed the above cost estimates.

[2] See estimates from: USFS 10-25 BDT/acre (2022); Blue Forest Conservation 14.3 BDT/acre (2025); LLNL 15 BDT/acre (2020). Slightly lower estimates include: UC Berkeley 7.3 BDT/acre (2021), although this assumes treatments slightly less than 1 million acres per year and includes an economic feasibility screen.