Aligning GGRF with the 2022 Scoping Plan

California’s Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund (GGRF) generates roughly $4 billion annually for appropriation by the Legislature to support the state’s climate goals. However, a majority of these investments were set and have been unchanged since 2014. This is over two Scoping Plans ago (2017, 2022), before the IPCC’s 1.5°C Report and even before the Paris Agreement was signed.

As policymakers consider cap-and-trade reauthorization it makes sense to review current GGRF allocations in light of the latest available science. In this blog we evaluate the alignment between current GGRF allocations and the 2022 Scoping Plan. We find there is a significant mismatch – including that arguably none of the continuous appropriations (65%) are priority investments for the state’s climate goals. The remaining discretionary appropriations (35%) are somewhat improved although they are spread thinly across 79 programs at 19 agencies and could be more targeted to climate priorities. We outline a potential net-zero GGRF investment framework that covers four broad categories:

40% ($1.6 billion/yr) to clean energy infrastructure, including electrical transmission lines, ZEV charging stations, and hydrogen and carbon dioxide pipelines and storage sites;

35% ($1.4 billion/yr) to an affordable transition program, including energy cost reduction and reliability strategies, regional workforce development and related community investments, and where appropriate fossil fuel asset decommissioning and site remediation;

15% ($600 million/yr) to emerging technologies, including certain clean firm power, long-duration storage, clean fuels including hydrogen and sustainable aviation fuel, direct air capture, and other industrial decarbonization; and

10% ($400 million/yr) to natural and working lands, including primarily wildfire prevention as well as land acquisition and similar strategies that limit urban sprawl.

GGRF investments serve multiple important state priorities and we recognize this analysis is more narrowly focused on greenhouse gas emissions reductions. However, there is a risk that California will fall short of its climate goals without revising current GGRF allocations. A revised plan can continue to achieve key goals including ensuring secure and high-paying jobs for workers as well as driving major investments in disadvantaged communities – albeit with improved climate outcomes.

***

California’s ambitious climate goals require the deployment of enormous amounts of new clean energy, including solar, offshore wind, batteries, transmission, zero-emission vehicles, hydrogen, carbon removal and more in only two decades. Although state leaders have adopted important new policies in recent years, there is evidence that we are currently not on track to achieve our 2030 and 2045 climate goals.

The Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund (GGRF) is a key source of funding to deliver the state’s climate goals. The GGRF generates revenue from cap-and-trade auction proceeds, including over $4 billion per year in recent years. The Legislature then has the authority to appropriate these funds with the main goal being “to facilitate the achievement of greenhouse gas reductions in the state".

However, it has been over a decade since the majority of current GGRF allocations were set by the Legislature. This precedes multiple key policies and plans, including SB 32 (2030 GHG target), AB 1279 (2045 GHG target), SB 100 (100% clean electricity), the 2017 and 2022 Scoping Plans, the SB 100 Joint Agency Report, CAISO’s 20-Year Outlook, CEC’s Offshore Wind Strategic Plan, CNRA’s Climate Smart Lands, Wildfire Action and 30x30 Plans, CARB’s Advanced Clean Cars, Trucks and Fleets rules as well as SB 150 report, Executive Order N-79-20 (100% ZEV sales by 2035), and many more.

As the Legislature considers cap-and-trade reauthorization in 2025 it makes sense to review current GGRF allocations to ensure their alignment with the latest available science. In this blog we summarize key information related to current GGRF expenditures as well as findings from the state's most recent climate plans to help inform stakeholder discussions related to cap-and-trade reauthorization.

Recap on how GGRF is spent today

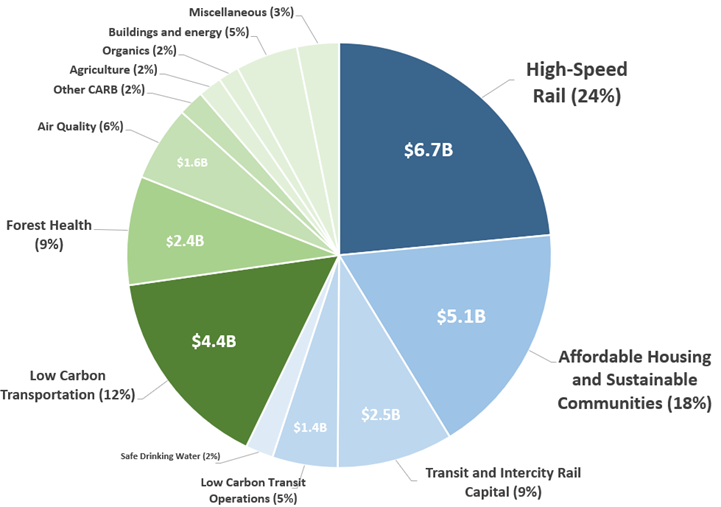

Since 2014, GGRF investments have supported multiple important state programs. As of May 2024, a total of $27.5 billion has been appropriated to 90 programs across a range of issues including rail and transit, affordable housing, forest health, air quality, agriculture, building decarbonization, and more.

Figure 1 summarizes these allocations in more detail. Highlighted in blue are programs that receive annual (or 'continuous') appropriations based upon mandated percentages (%). These were established in 2014 according to SB 862. Key continuous programs include High-Speed Rail, Affordable Housing and Sustainable Communities, and Transit. Highlighted in green are programs that receive discretionary appropriations. These are subject to change each year and there is no guarantee that programs receive recurring funding. Key discretionary programs include Low Carbon Transportation (i.e., multiple programs focused primarily on incentivizing ZEVs), Forest Health and Community Air Quality Protection.

Figure 1: Allocation of total GGRF appropriations ($27.5 B) to May 2024.

The question at hand is whether it is appropriate that these programs continue to receive the same allocations through to 2030 and potentially all the way to 2045, assuming the Legislature seeks to reauthorize cap-and-trade in accordance with that timeline, or whether there should be a change. Our goal is to evaluate this question through the lens of achieving greenhouse gas emissions reductions.

For more information on current GGRF programs, including estimates of portfolio cost-effectiveness, see our article: Data analysis of California's Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund.

Reviewing California’s main climate plan

As a means for comparison we review the 2022 Scoping Plan, which is the state's main climate document that identifies the actions and outcomes necessary to achieve both 40% emissions reduction by 2030 and economywide net-zero emissions by 2045. The Scoping Plan is a reliable source document given it reflects the latest available data and science and incorporates consideration of other state climate plans and policies, including from the CEC, CNRA, CPUC, CAISO and Administration.

Figures 2 and 3 provide key summaries of the state’s planned energy transition. Figure 2 shows the change in energy mix from 2020 to 2045. Figure 3 shows the energy end-uses by sector in 2045.

Figure 2: Anticipated change in California's energy mix from implementing the Scoping Plan scenario.

Note: Please click on the image to expand its size.

Figure 3: Flow chart showing the proportion of clean energy demand and end-uses by sector in 2045.

Note: Please click on the image to expand its size.

We highlight a number of key takeaways:

An unprecedented expansion in clean energy is key to the state’s climate goals. This technology deployment spans three key areas:

Supply: Figure 2 shows a significant expansion in clean power, primarily utility-scale solar and batteries. There are also needs for long-duration storage and clean firm generation such as geothermal and natural gas with carbon capture and storage. Clean fuels such as hydrogen, biomethane and sustainable aviation fuel are needed to help smooth the transition as well as address hard-to-electrify end-uses.

End-use: Figure 3 shows the key end-uses that drive decarbonization in transportation (ZEVs, renewable diesel, sustainable aviation fuel), buildings (heat pumps, induction stoves) and industry (various electrification, fuel switching). Clean power is also needed to enable a significant amount of carbon removal to address residual emissions.

Infrastructure: Clean energy infrastructure is the linchpin to delivering the Scoping Plan scenario as it connects energy suppliers and end-users and enables offtake agreements. Key infrastructure needs include electric transmission lines, ZEV charging stations, and hydrogen and carbon dioxide pipelines and storage sites.

Figure 2 shows an important but sometimes neglected aspect of a net-zero transition, which is the rapid phase-down of fossil fuels. This is necessary for climate goals but will negatively impact some workers and communities. It is important that the transition is executed in a way such that energy remains accessible, reliable and affordable and that affected workers have a clear line-of-sight to secure and high-paying alternative employment in the same region. If these factors cannot be met, there is a risk of undermining the state’s net-zero transition.

Current continuous appropriations (65%) for High-Speed Rail, Affordable Housing and Sustainable Communities, Transit (see note below), and Safe Drinking Water, while important for multiple reasons are not identified as priority climate investments in the 2022 Scoping Plan.

Current discretionary appropriations (35%) are more consistent with the 2022 Scoping Plan, although there is room for improvement. For example, ZEV incentives under Low-Carbon Transportation are important but come at a high price tag. Forest Health is a priority area and should retain investment (see note below). Recent new industrial programs at the CEC are small yet aligned with the Scoping Plan. Setting eligibility requirements for discretionary spending is likely to improve overall cost-effectiveness relative to an annual ad hoc approach.

A note on Transit and Vehicle Miles Traveled (VMT)

The transportation sector is the state's large source of emissions. Vehicle electrification and the use of clean fuels are identified as the primary strategies for achieving decarbonization. The Scoping Plan also identifies a need to reduce per capita car travel (VMT) by 25% by 2030 and 30% by 2045, which cannot be achieved through vehicle electrification and the use of clean fuels. The Scoping Plan identifies a number of potential policies that, if carried out by the relevant state or local agencies with the required planning or land-use authority, could enable the target VMT reductions. These policies would support an increase in public transit and active transportation (walking, biking), amongst others.

A note on Natural and Working Lands (NWLs)

This analysis focuses on anthropogenic emissions although it is important to note the role of NWLs in achieving the state’s climate goals. Specifically, the Scoping Plan finds that even under ambitious land management assumptions the state’s NWLs are likely to be a net source of emissions in 2045. This finding is driven by wildfire, which has proven to be the state’s largest source of emissions in recent years. It will therefore be important to implement the state’s NWLs targets, notably wildfire prevention, to keep the state’s NWLs as small a net-source as possible through to and including 2045.

Net-Zero GGRF Investment Plan

The previous sections show a large mismatch between current GGRF allocations and the actions and outcomes identified as necessary to achieve the state's climate goals. In this section, we outline a potential revised GGRF investment framework that is targeted to implementing the 2022 Scoping Plan.

Background

As there is some subjectivity in translating a document such as the Scoping Plan into a potential investment strategy, we highlight the key considerations that guided our approach. First, is that we did not include technologies that are mature or robustly supported by other policies. For example, utility-scale renewables are supported by CPUC procurement processes while other low-cost options should be incentivized under the cap-and-trade carbon price. Second, is that we prioritized infrastructure that is often high cost and difficult to develop but key to eliminating bottlenecks. Third, is that we sought an investment plan that could continue to drive investments in disadvantaged communities. Lastly, we avoided a sectoral approach (i.e., proportioning investments based upon current sectoral emissions) due to the cross-sectoral needs of the same clean power, fuels and carbon removal.

Summary

An overview of a potential Net-Zero GGRF investment framework is provided in Figure 4. These investments could be made continuously or on a discretionary basis with guardrails or eligibility requirements. Although the implication of cap-and-trade reauthorization is for 2030 onwards, it would be more beneficial for state climate goals to implement a revised GGRF strategy sooner than this time.

Figure 4: Summary of a Net-Zero GGRF Investment Plan

We briefly summarize each of the four investment areas below.

Clean energy infrastructure (40%)

California must develop hundreds of billions of dollars worth of new clean energy infrastructure to meet its climate goals. It is important that these projects are prioritized in order to enable related technology deployment, such as new clean generation, ZEV purchasing and carbon capture retrofits. However, large-scale linear infrastructure are high-risk projects that are difficult to finance and deliver. Recent analysis shows that, even if they can be financed, the risk premium that flows to developers results in significant costs being passed on to consumers. GGRF investments can serve to de-risk this infrastructure development and keep costs low for consumers. As many infrastructure projects (transmission, pipes, storage) generate revenue they are also good candidates for green bank activities, such as revolving loans, which can substantially multiply the impact of public investments.

Affordable transition (35%)

A credible fossil phase-down strategy is essential to delivering a net-zero transition. This cross-cutting investment area would seek to enable the transition by supporting clean energy workforce training and development, energy cost reduction measures (e.g., funding for: non-essential utility programs such as wildfire mitigation; adequate analysis and oversight of oil and gas prices and related program implementation; and an adequate strategic reserve to ensure grid reliability during extreme weather events), and related community investments that would indirectly support a regional workforce transition. Where appropriate, funds could also support fossil fuel asset site remediation (e.g., permanently sealing abandoned oil and gas wells; other remediation). Funds could also support future large-scale transition needs that may occur on a 'lumpy' basis, such as refinery or power plant early retirements or closures.

Emerging technologies (15%)

The Scoping Plan identifies needing to scale multiple newer and higher cost technologies in order to achieve deep decarbonization and net-zero, including clean firm power, long-duration energy storage, clean hydrogen derived via electrolysis and waste biomass, sustainable aviation fuel, direct air capture, cement decarbonization as well as other industrial decarbonization. Some of these technologies have access to partial incentives, but many do not. Where existing incentives are available, the state could provide funding as part of a Contracts for Difference mechanism that provides revenue stability for developers while optimizing the amount of GGRF funding that is committed to emerging technologies.

Natural and Working Lands (10%)

California's NWLs are currently a net source of emissions due to primarily catastrophic wildfire. In 2020 alone, wildfire emissions (100 Mt) were greater than the amount of anthropogenic emissions the state had reduced in total since the passage of AB 32. The Scoping Plan identifies needing to treat 2.3 million acres per year for wildfire prevention. This is a monumental task, with an expected cost of roughly $6 billion per year – about the same size as the entire annual natural resources budget. A circular bioeconomy producing clean fuels and carbon removal has been identified as a key strategy, but a recurring source of GGRF funding can provide near-term support. Other NWLs strategies that could provide large emissions reductions include acquiring and placing land on urban peripheries into conservation easements. This funding could support strategic investments led by local governments.

Conclusion

California's Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund is a key investment program to help meet the state's climate goals. However, many of the current appropriations were set and have been unchanged for over a decade. While it was appropriate at that time, the latest climate plans show that current GGRF investments are not aligned with the actions needed to achieve the state's 2030 and 2045 climate goals.

There is a risk that California may fail to meet its climate goals without revising GGRF investments. We reviewed the 2022 Scoping Plan and, based on the findings and recommendations in that report, proposed a net-zero GGRF investment framework. Key investment areas include clean energy infrastructure, affordable transition strategies, emerging technologies and natural and working lands. A net-zero approach to GGRF can continue to prioritize investments in disadvantaged communities and provide secure and high-paying employment for transitioning fossil fuel workers.

Although the current cap-and-trade reauthorization discourse implies that any policy changes would take place from 2030, it would be more beneficial for state climate goals to revise GGRF sooner than this time, given the large mismatch between current appropriations and actions needed for net-zero.

For more information, please contact Sam Uden (sam@netzerocalifornia.org) and Amanda DeMarco (amanda@netzerocalifornia.org).